India: the good, the bad and the puzzling

After our first trip to India I wrote down my questions and thoughts in a post I titled “Liberty for all?” A friend with a more positive view of the place thought that my criticism was a little too harsh. My views about India did not change fundamentally, I still think that they are not ready for ideologies requiring a high degree of individualism (such as libertarianism) but I am not as sure as I was after our first visit. India tends to bring out strong reactions from people. I know some who hated it, many who would never return. We’ve been there three times. Indian culture has some aspects that I do not like or in some cases find outright irritating, but at the same time the culture mostly fascinates me and helps me formulate a number of important questions affecting not only their culture but ours as well. The greatest source of my fascination is the diversity of the cultures. Our first trip introduced me to Muslim, Hindu and Jain cultures. The second trip was even more fascinating in its cultural aspects. We started in Buddhist India then we went on to Muslim, Sikh then Hindu India again. The contrast between them was striking. In this third one, we went deep into Hindu India in Tamil Nadu then got a little exposure to Christian India in Kerala and Goa, but this post is not about the different cultures, languages and religions of India. Throughout all three trips but especially the last one I kept wondering how can that messy place function, how can it grow, what possible future can it have. I am not the only one. When people write about Asia, they usually contrast China with India. Fareed Zakaria, the Indian, in his book “The Post American World” was betting on China. Economically, most people do. Culturally, the question is more open. Nobody knows which system will survive and what can either possibly morph into. I don’t think I have the answers; all I can offer are my impressions and some questions.

The Good

There are many things I find likeable, many things I wish we had more of ourselves. Family values are still pretty strong in India. Divorce rates are still amongst the lowest in the world but marriage is not my concern at this point. I have the feeling that people are relying less on the state for support in their old age than they do on their families. The idea that you owe it to your parents to take care of them in their old age is far stronger than in any other culture I know. We could debate the good and bad aspects of arranged marriages, two income families and divorce rates, but I find this sense of intergenerational responsibility an excellent thing to have for a healthy civil society. India has a strong, affordable private school system that is relatively free from political interference. Nobody in the middle class would entrust their children to the government schools. “We have free schools” – a friend said – “but everybody in our position (affluent middle class working in the IT industry) would send their kids to private schools.” It costs about a thousand dollars per year to do so. Investing in your children and expecting them to take care of you in your old age frees you from what is the two most intrusive government services in the developed world. Add to this a health care system which works very much like the schools: free if you can’t afford it, much better quality if you can. With this three you are half way toward a libertarianish sort of world. Well, I wish it was this simple, but I hope you get the point. Although India is a fundamentally socialist country, most of its economy is beyond the control of the government (only 5% of all Indians pay income tax). As they are climbing out of poverty the state is not organized enough to strangle these free market responses to the poor quality services it provides. As Gurcharan Das points out in this speech, India has a strong society. That is its best chance and best advantage, just as it could be its greatest hindrance making it a lot more difficult and slow to change. The next thing I like there will earn me the ire of libertarians – my liking of it, that is. They are almost halfway through with the implementation of their extremely ambitious biometric ID system. It is highly controversial in the media both within and outside India, yet 40% of the population already have it and it seems to be a popular idea with them. It promises more personal accountability which in turn may spur stronger economic growth. Although the Orwellian risks of such system are significant, the potential benefits can be tremendous as well. The book I took with me for the road was Hernando de Soto’s “The Mystery Of Capital” extolling the benefits of properly documented and protected property rights. The biometric ID system may help to bring that about. At this point I am willing to give it the benefit of the doubt putting it into the positive side of the ledger. The Japanese are perfectionists, the Chinese are diligent, the Indians are competitive. The world’s richest man is Indian. Indians in the diaspora are more successful than any other immigrant group. They thrive on foreign soil. They are the highest earning ethnic group in America. This Business Week article offers some possible explanations why. The puzzling question to me is how can they be so successful here and despite all the progress, still so wretched at home?

The bad

India is hopelessly corrupt. Not disastrously corrupt like Somalia or Afghanistan, but I’d say corruption in India is more culturally ingrained. The fact that I was taken advantage of as a tourist did not surprise me as it is in the nature of being a tourist, but I found it disheartening to see how Indians can take advantage of each other. One possible reason is the cultural inheritance; the cast system, the society that was built on the social units of village – cast – extended family that locked accountability, reputation, cooperation into very small units. As the population of the country exploded, the loosening of these binds created a highly uncivil society. Coming from a generally polite and considerate world, the difference is striking. The point in this, again, is that political corruption is just the symptom, the manifestation of a much deeper problem. India also has the dubious distinction of having the first democratically elected state level communist government in the world. (Kerala, 1957). Although their influence is fading, communists were also a major political force in Bihar. While Indians do not trust corrupt politicians, they still have a surprising level of faith in politics and their political ideas are to an alarming level left leaning.

The puzzling

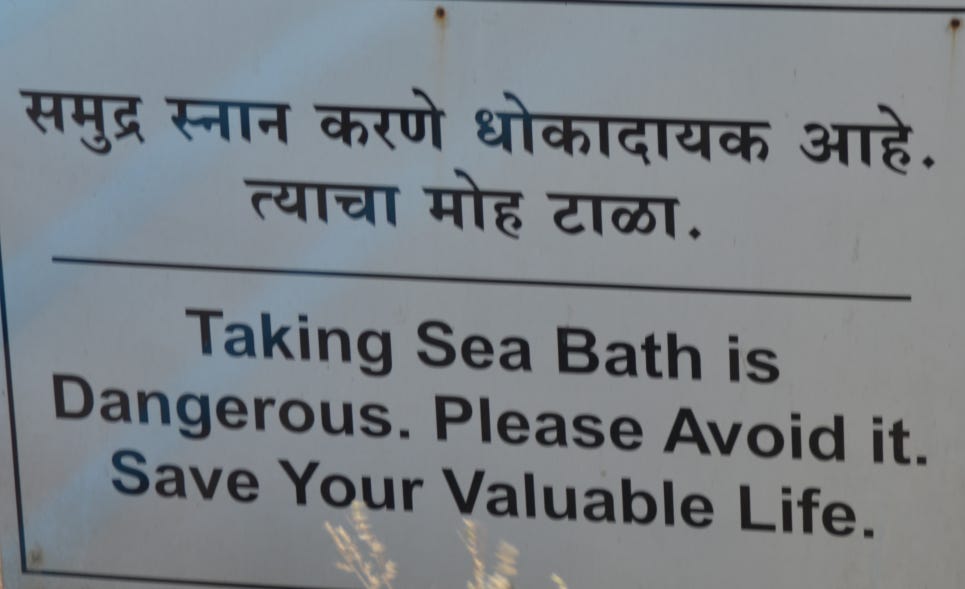

Indians are very different from us. The most striking to me is their lack of interest in physical activities. They watch cricket the way we watch baseball but they do not have the variety of spectator sports we do. Indians do not hike, swim, bike or run for fun. Ten million people Hungary has an accumulated total of 482 Olympic medals. Thirty three million people Canada has 423. Over a billion people India has 26. Olympic medals may not be the best measure as most developing countries are quite behind, but still, I cannot help the impression that with the notable exception of cricket, Indians, it seems, just don’t do sports. On our first trip I made the mistake of renting bicycle for a few hours. It was horrible. No way to adjust seat height, no derailleur, bad brakes. On our last trip I was on a mission to find, to at least see a good bicycle. Not a chance. I found pretty ones, the new styles with the thick tube frames, I even saw some with shock absorbers but I did not see any with more than one gear. The only invention on a bike that would make some sense for someone hauling weight. I never saw an Indian swimming. They may wade into the water, but that’s it. I saw this sign, though:

They did not have to put the word swimming on the sign. It wouldn’t cross anybody’s mind to try that. Extreme sports? Para-sailing and sea-doos. (yes, I AM sarcastic) I do not like to be served. Indians seem to love it. In Canadian airports the services of porters are used almost exclusively by Indians. It is also typical in Indian restaurants to have 3-4 waiters waiting on your table. It happened to me twice in our last trip that I had to ask a waiter to go away because it made me feel uncomfortable him standing around staring at us as we eat. I cannot decide how much of what I described as curiosities have anything to do with culture. My grandparents never went on vacations, but if they did, there would have been porters at the train station. There were no old-age homes for their generation. My parents never went on vacation either. They weren’t pursuing a particularly sporty lifestyle. For my generation, being born out of wedlock was still a stigma. I finished elementary school knowing a single person whose parents were divorced. Maybe India is just behind us. It is possible, that what I saw as the positive aspects of Indian society are also bound to change the same ways ours did. When I am puzzled about Indian culture, I always have to contrast it with my own about 50-60 years ago, then ask what the likelihood that this one will evolve differently is; then ask what could make the difference. I was also puzzled by the economy. A typical Indian ‘business’ is a 3x3 meter hole in the wall. Some do skilled work but most do not. They are mostly small resellers or service businesses. In tourist places we can see whole armies of small vendors selling essentially the same things. They are all low volume producers with obviously low income. Most of the visible life on the Indian street seemed like an economic trap of low skill, low income, not much future. I kept wondering what will happen to them as the economy grows. Will industrial production absorb them? Just as we are exiting the industrial age? The only thing that can make an economy grow is growing productivity. How can these people possibly increase their productivity? Will the emerging middle class have enough income to afford this low skilled class a higher income? Will the Indians’ love of being served offer them an easier transition into a service economy? Hardly anybody in the developed world goes to a barber for a shave any more. Will Indians retain those jobs more than we did? This is a question – what will happen to low skilled workers - that the developed world also have to face at some point, but the problem felt more acute to me in India. In the end, I came away with more questions than answers, definitely more than what I can fit into one post. I will continue with two more questions addressing the two aspects of the Indian world that I found the most intriguing and distressing in all three of our trips. In the meantime, here are some links for your consideration. About the changing divorce rates in India. About a school voucher program in Andhra Pradesh (The writer is clearly biased against vouchers but at least honest in reporting theresults.) A book of Gurcharan Das: India grows at night and a fascinating discussion about it at CATO …and of course, the book of De Soto “The Mystery of Capital” If you want to understand Indian culture, you should read V. S. Naipaul. He is a Brahmin born in Trinidad which gave him a very interesting perspective. He wrote several books about India, I read only An Area of Darkness and India: A Wounded Civilization Still on my list is the third one in this series: India: A Million Mutinies Now