I had no compelling reason to tell this story before, but I got to a point now, when there are several things I cannot appropriately address in this blog without referring to it. Most of what I think about criminal justice and law enforcement is influenced by my own jail experience. On March 15th 1972 when I was 19 years old, I was arrested, charged and convicted of the crime of “continuously and publicly perpetrated sedition against the established order of the Hungarian People’s Republic.” I was sentenced to one year in a maximum security prison; I was paroled after serving nine months. On the big scheme of things, this was a ridiculously insignificant little incident in the history of communism. Some of my co-conspirators are still interviewed about the events time to time but what happened matters only to those whose life was disrupted by it. I will try to be short but still long enough to be able to make my points.

Background – me

I was born in 1952 right at the height (or depth, rather) of Stalinism in Hungary. Both my grandparents were in the middle/upper middle class before the war and got completely dispossessed by the communists. One of my early childhood memories was the emotional moment in 1956 when my then 16 years old uncle said goodbye to us before heading to the Yugoslavian border which was the last to close as the soviets retook control over the country. He ended up in Montreal, following him is how I ended up in Canada myself. My father, who did not raise me, was jailed after the revolution for two years; he was never allowed to finish university and spent his life as a coal miner. I was growing up in a fairly apolitical environment. The message I received from just about anywhere was that I had to conform. I was also the product of the system, a member of the communist youth organization. It was kind of obvious to all of us that the system does not work, but nobody around me had a doubt about its inevitability. We all believed that this is the future and we have to find our place in it, we have to learn to fit in. At sixteen, I spent my time with my friend trying to reconcile the Marxist ideas with the Leninist reality. Another group of my friends (children of a group of communist idealists) were looking at alternatives to our own ossifying system, but always communist alternatives from the Euro-communism of Gramsci through the Latin American revolutionary communism of Castro and Guevara all the way to Maoism. I had no answers myself, but I did not consider myself the enemy. I saw myself as the loyal opposition, as someone who would like to make the system work.

Lesson #1: There is no such thing as loyal opposition in ANY autocratic system. One either submits completely and unconditionally to the operational rules of the system or he is the enemy. One cannot get anywhere without conformity and devotion to the power AS IT IS. Once you attain power in the system it is possible to express different views but those views should not be too openly ideological, should not question any foundational element of the system; they could only represent differences in managerial style.

Again, I did not see myself as the enemy, but I was young, naïve and an idealist.

Background – the place and the time

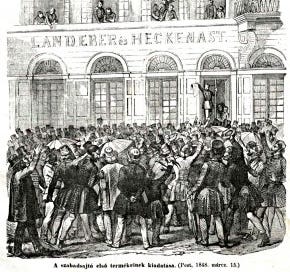

The most important national holiday in the Hungary I grew up in was March 15th, the anniversary of the revolution and war of independence of 1848. We learned in school about every single event of the day, memorized the demands of the revolutionaries and recited the ‘Nemzeti Dal’ (National Song) – the poem Petőfi wrote for the very occasion on the very same day. It is the most glorious day of Hungarian history, the centerpiece of Hungarian National identity. This was also the only holiday that was not fundamentally communist in nature such as ‘Liberation day’ (when the soviet occupation was completed at the end of WW II), the communist ‘Constitution day’ or the anniversary of the glorious Soviet revolution. Celebrating March 15th was one of the last bits of national identity in the relentlessly growing communist internationalism around us. Until 1970. Our rulers decided then that the commemoration of this event does not warrant a public holiday and it ceased to be one. It became a regular school and work day with only heavily toned down official events to celebrate it. The change was abrupt and was not very well received. I heard rumors in 1971 that some people were arrested in spontaneous demonstrations but did not pay much attention to it. I was too busy living my life.

The day

March 15th 1972 was a beautiful spring day. The first warm day of the year. I agreed to meet someone downtown in the evening but I left home three hours early thinking that I will just walk around downtown. I had no idea that there will be a demonstration; I had no plans to participate in anything and I had no idea what else has happened in the city earlier that day. When the streetcar stopped at the National Museum which was the focal point of the events 124 years hence, I saw a small crowd. Since I had nothing else to do, I got off to learn more. There was nothing to learn. Nobody seemed to know anything. It was a spontaneous gathering without any goals or directions, only gathering at that place because of the historic significance of the location. At some point a chain message started suggesting that we will go to the castle hill, again, just a reenactment of the historic events. By that time there was a heavy police presence around us. It was a crowd going through the motions but without any organization, any real plan or leadership. We did what would have been perfectly normal just two years before with public officials leading the events. Only now, it was illegal. This was NOT the 56 revolution and not the repeat of the 1848 one. In the course of the ensuing trial and the years after I found no evidence whatsoever of subversive intentions. Yet, it seems that our communist rulers were petrified. They could not allow for the existence of anything unplanned and uncontrolled.

Lesson #2: a dictatorship cannot afford to tolerate spontaneity even if it is not hostile, even if it represents spontaneous support for the system. Anything unplanned is a threat to the basic principle of a planned and controlled system, (Read the footnote for an example at the bottom of this page)

As for me, once there, I was in. with all the righteous idealism of a 19 year old. I did things that were turned into serious points of the indictment. When we were about to leave the steps of the museum, I stood up and said ‘Rise, Hungarians!,’ the first line of Petôfi’s poem. It was a joke. People laughed. As we marched, people sang songs of the revolution. Well, not really. They didn’t know many, they were just repeating the same and since I knew many more, I ended up ‘leading’ the singing. Both of these were made me look in the indictment as some sort of leader of what was happening. As soon as we were on the move, the police got into action. First they cut up the larger group of a few hundred people by cutting into it and directing parts in different directions. Once they managed to isolate people into smaller groups, they started beating them up. I only witnessed a few; I was not subject to one. Eventually, I ended up crossing the Danube with maybe two dozen people and arrived to the foot of Castle hill where we merged with other small groups to about 100-150. We had two possible ways to go up, headed in one until some people who were ahead of the group were running back saying that there are policemen around the corner. The whole group turned to take the other route up. Except me. I was left alone continuing in the ‘original’ direction. I am not doing anything wrong – I thought – I am walking alone on the streets of my home town. Around the corner two policemen stopped me asking for my papers. I gave it to them. ‘Go home they said.’ Why? ‘Because we beat the shit out of you if you don’t.’ They handed me my papers, I took a 90 degree turn to cross the street then I turned again to my intended, original direction. When they realized that I am trying to get around them, they charged me swearing, batons raised, clearly intent on a beating. I turned and said “Fascists” then I ran. One of them did not hear what I said, he had to ask the other which gave me a few second head-start. They did not stand a chance catching me. Eventually I arrived to Trinity Square (Szentháromság tér) to find there maybe 2-300 people. It was interesting to see that crowd. It was less cohesive and a lot more cautious than the one at the museum. As if everybody wanted to observe from the outside. It did not work too well. The police came in force; about a hundred and fifty of us got arrested. One of the two policemen I encountered before recognized me. Then the process began. I could have told you the story in more detail, but you have here everything that mattered. Think what you will of my stupidity and cockiness but keep in mind that it is not the point. This is not about me, but the system.

The investigation

The crowd was not the only one without direction. So was the communist state. They clearly did not know what to do. Nothing really happened; there was no real enemy, nobody with a goal or a plan. Yet they clearly had to put a stop to it. The system couldn’t afford and couldn’t handle spontaneous events like this. They picked eight out of those arrested for a show trial to make an example out of. I was one of the eight. The case got escalated very quickly. When I was arrested, they took us to a district police station. From there we were taken to the police headquarter of the city. Within 5 days, we were transferred to Gyorskocsi utca, the top facility in the country to investigate political crimes. The rank of my investigating officer was Lieutenant Colonel. We were taken VERY seriously. Interlude:

When I got to the police HQ, where all arrested ended up, I got lots of unwanted attention. I was young and poor, living on my own. I had one pair of shoes, a cheap felt-top one that got a hole on it in the winter. To cover the hole, I took a piece of red felt, cut two red stars out of it and glued it on to cover the hole. Obviously, everybody I knew asked me what that is about so I told them that I had to cover a hole, and since every hole in this country is covered with ideology, my shoes should be no exception, BUT – I continued – if any policeman or official asks me, I will tell them that I chose the stars because those red stars are guiding my steps. This was the ONLY conspiratorial element in this whole case and the ONLY thing the authorities did not get me for. Everybody I knew, everybody the police interviewed as a witness was familiar with both narratives yet the damaging one never came out. I am sure that if it did, my sentence would have been at least twice of what it ended up to be. The fact was still part of my indictment but only with the ‘official’ explanation.

The investigation was very instructive. I was not tortured, I was only beaten once and even that was not very serious. It was actually funny. It was done by the first policeman who interviewed me. He asked me why was I brought in. Because I called two policemen fascists, I said. Whaaaaat???? He said. FASCIST?? THE POLICEMEN OF THE HUNGARIAN PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC?? Then he started hitting me presumably to prove how wrong my assessment was. In the end, however, he wanted to let me go charged with a misdemeanor punishable by one month in jail but no criminal record. It was the attention paid to my shoes by other investigators that kept me there. For the longest time, I did not want to believe what is happening to me. I was expecting at any time that I will be scolded and sent home with some stern warning. It took me a few weeks to realize that this is serious, that I may actually go to prison. The investigation lasted about two months after which we were transferred to the courthouse jail waiting first for the indictment then for the trial. Reading the indictment was the first time I learned the names of my co-conspirators. I did not know any of them, only 2x2 knew each other. The system tried hard to pit them against each other but without much success; not because they lacked the power but because there was nothing to work with. Absolutely innocent activities were suddenly judged to be criminal. It was not about the acts but their interpretations. We were sentenced for projected intentions and misrepresented acts. A point of accusation against one of us was distributing copies of a poem that was a staple part of official celebrations. But then, that was a different context.

Lesson #3: Context is an essential element in the exercise of discriminative political power. Look around yourself in Canada in 2012. What you can or cannot say depends greatly on who you are, where and when you say what you do.

Communist legal practice

We were all young, we were all fooled. Maybe we were just all stupid. We did not know the law; we did not understand that we had no rights whatsoever, that we were completely at the mercy of the investigators. We had no right to legal counsel until the indictment. We had no understanding of the process. The police created a transcript of each session of the investigation, to be used later in the trial. The policeman asked me a question, rephrased my answer, typed it on a type writer in the first person then when the session was over, handed it to me to sign it. Somehow, for some strange reason they never got it right. The words that were put in my mouth always sounded much worse than the ones that actually came out of it. If I really insisted that he should retype it, he did it, but made it very clear that he is not pleased by my lack of cooperation and somehow the end result was even worse. I learned fairly quickly that there is no point pushing too hard and told myself that it can be fixed in the court. There were a few messages they were selling to us:

They are just a little gear in the machinery, what they do does not matter that much.

On the other hand, considering the serious nature of our crimes, the only thing we can hope for are the mitigating circumstances such as our level of cooperation with the investigation. Their good will can help us, but if we are difficult, their recommendation can hurt us just as much.

The investigation is not the most important part of the process if they get something wrong, we can always correct it when we get our day in court

Lesson #4: never ever trust a policeman. Anywhere. I will tell you stories about my bitter disappointment about Canadian ones. Policemen live in their own world with its own rules that are not much friendlier to the victim than to the criminals while seeing everybody in-between as a potential criminal.

What we did not know, was that the court had an absolute discretion on what to consider as evidence, the transcript of the investigation that we were coerced to sign, or what we said in court. As we were waiting for the trial in the court’s jail, we had a closed circuit radio show twice a week. One of the regularly repeated segments we had to listen to was advising us about the indictable crimes that we should avoid committing while in jail. Worst of those was slandering an officer of the state. Making any statement, any accusation that we cannot prove would be punishable by one and half year in jail. The judge played this card on us with playful abandon. “This is not what you said during the investigation. Were you forced to sign it?” We were not allowed to retract anything. We were suckered big time.

The trial

I could talk about my partners in crime, about the indictment, what it meant and what it tried to achieve. You should trust me when I say that the crimes of my co-conspirators were about as serious as mine. I got into it truly by accident while some of them went there for a reason, guided by their indignation about the devaluation of this national holiday, by their desire to celebrate it publicly. None of them had disruptive intent, they did not go to protest; none of them thought that anything they did could possibly be interpreted as hostile toward the state. Spite, maybe. Hostility, no. Their stories are just as interesting as mine, but to keep the story simple I will keep focusing on my own ‘crime’ and its treatment by the court. What got into the indictment was quite substantially different from what actually happened and different even from what got into the transcripts of the investigation. According to the indictment, I was marching at the head of a 150 strong hostile crowd when we encountered the two policemen whereupon I shouted “Fascist terror-gang” with the clear intention of urging the crowd to attack them. This made a big difference. The sentencing guideline for sedition was up to one year, but if perpetrated in public, in front of a larger audience, this changed to 1-8 years. The point in this was a perception of the sentence. One year would have been the maximum sentence for the lesser offense. By giving me the minimum sentence for the more serious crime, the state demonstrated its benevolent and merciful nature. I got a court appointed lawyer. He was sitting through the procedures diligently except the one day when my witnesses were called. He just happened to be late and missed the chance for a cross examination. Not that it would have mattered. One of the eight of us had a very good lawyer completely destroying the testimony of the policeman, which was the only evidence against him. The judge chose to ignore the result of the cross examination and it was left out of the court transcript entirely. I checked the transcripts before the appeal trial. They were prepared exactly the same way as the transcripts of the investigation, only this time the phrasing was that of the judge.

Lesson #5: Jurisprudence does not mean justice. Strict adherence to the rules of procedure usually denotes a system without self-confidence, without faith in its own ability to serve justice.

Lesson #6: The most effective way to eliminate justice is by making the laws meaningless. The communists seldom broke the law. They just created laws and rules that allowed them to do whatever they wished.

I almost felt sorry for the policemen testifying against me. One had a script that he was supposed to memorize and he just couldn’t. The judge had to help him to keep him on script. Still, his testimony had several contradictions. Since my lawyer was not there, I was allowed to ask questions. After my second question when it was clear that I will catch him on a lie, the judge ordered me to sit down saying that my questions are irrelevant. All of my witnesses, all of my friends were wonderful. That didn’t make a difference either. The whole trial was a circus. When the judgment came through and the sentencing was announced, four of us (from the six in custody) were released pending the result of our appeal. The appeal trial took place three months later; all sentences were either upheld or made harsher but not significantly. I had to start the remainder of my sentence a few months later.

End notes

The court was open, filled mostly by friends and relatives of the eight of us. When we were let go after sentencing, most of us were waited for outside. A relative of one of the eight came to me to shake my hand, to congratulate me for my brave behaviour. It made me feel embarrassed. I did not think I was brave. I played along. I did not display fear, remorse or submission, but I did not stand up. I did not call the policemen liars, I did not protest when the judge allowed in my witnesses without my lawyer present, I did not question the legitimacy of the whole charade. Having done so, I would have ended up with a far more serious sentence. I compromised; I accepted the rules of the game. It made me ask myself: can we call the lack of fear bravery? The lack of heroism cowardice? Is it brave running head-first into a brick wall? Could I have done any better? Was I a victim or a collaborator? Doesn’t the lack of principled opposition equal collaboration?

Lesson #7: Sometimes even victimhood can be complicated.

My next post will be about the penal system of Hungary in the 70s. If you don’t want to miss it, click on follow. == === ==

Footnote - The story of spontaneous support

1918, only months after the successful revolution of the soviets, there was a short-lived communist revolution in Hungary. It started March 21st. It was a minor national holiday. After the events on the 15th that got me into trouble, five students of the faculty of law (two of whom I happened to know) decided to organize a counter-demonstration, a public commemoration of the communist revolution in show of support for the established order. The March 15th demonstration had too much of a nationalist tone in their eyes. Their efforts were thwarted before they got anywhere, the leader of the group expelled, two suspended for a year, two formally reprimanded. The decision of the faculty committee is a fascinating reading. If you read Hungarian, I will be happy to send it to you, which is by the way also true for both of my court judgements. (First degree and the appeal)

Like everything else on Substack, this is a reader supported publication.

You can help it by following or subscribing.

You can engage with it by clicking on like and/or commenting.

A ‘like’ costs nothing and is worth a lot.

You can help this Stack grow by sharing, recommending, quoting or referencing it.

You can support it by pledging your financial support.

Any and all of it will be much appreciated.