The deficit of imagination

We are facing another election where (I suspect) the majority of voters already feel uncomfortable with the choice they are going to make if they even bother to make it. Everybody across the political spectrum can sense this discomfort and many try to address it. I had some interesting conversations on the subject recently and I am following the efforts of the RaBIT campaign to deal with what they see as the democracy deficit. Is there a democracy deficit? If yes, what is its source? The input or the output? Lack of interest by voters, loss of confidence in our ability to affect change, low turnout, the plight of small parties having no chance to get in, the apathy about the chance of the democratic process to affect meaningful change……. or Lack of accountability by politicians, the bureaucracy, party politics, the scandals and the broken promises? Most initiatives seem to be concerned with the first. Most critics of the present system want to see more voters being more engaged, being more involved with the issues, more active, more partisan. My experience seems to suggest that this is not where the problems lie.

Proportional representation initiatives

The idea behind the ranked ballot initiatives is that the composition of the parliament is not representing the percentages of the popular vote. It is kind of obvious, that is how the system was designed. That is why we have electoral districts, this is why we vote for individual candidates, not parties. Elected politicians are supposed to represent their electoral district first, their party second. Ranked ballots would push the already skewed system even further in the direction of party discipline. Ranked ballots are overhyped. So are the others such as STV and various party-list proportional systems. Wherever they are practiced they do not produce better results either in the level of political engagement, better functioning political systems or a better economy. There is no equivalent of the political freedom index. I think we can find better ideas to improve democracy.

Term limits

Term limits are probably next in popularity to variations in the electoral systems. It is well know that career politicians are getting more corrupt and more statist over time. The introduction of term limits cannot hurt, but I do not believe that it can noticeably improve the system.

The election lottery

A friend presented me with a fascinating variation of the term limit idea. The problem, he says, are the career politicians. The ones who would do anything to get into power and to stay there as long as possible. The problem is the revolving door, industry and special interest groups pushing their henchman into power where they can serve the interest of their backers. The solution is simple: modelled after the jury system, have a pool of a few hundred qualified applicants for the job of member of Parliament and pull a number from that pool once every four years. Pay them well while in office, but once they completed their single term they should return to their civil life. The essence of the idea is to minimize the possibility of corruption.

Qualifying (training and certifying) politicians

Politics is the only profession that requires no qualification whatsoever. Not even a literacy test. In this speech at Idea City Preston Manning makes a case for his initiative to educate politicians. We could take his idea a step further suggesting that any candidate for any party should pass a competency test to prove that they understand their role as representatives with all its obligations and limitations. It could, possibly, ensure that we have better politicians, but I do not believe that the intelligence or education of our politicians is what ails our democracy. We should educate them for sure, but that is not what will solve the problems of our political system.

Restricting voters

I honestly do not understand the concerns about decreasing voter turnout. I understand the concern about what the fact of decreasing turnout implies – increasing disillusionment with the process and the system – but I do not understand how higher numbers showing up at the polls could possibly produce better results. One must wonder what makes them think that more people would make qualitatively better judgments than fewer. How could the quantity make a qualitative difference? How would more parties in the parliament create better politics? The only reason political parties and the media is so hung up about voter turnout is that they see it as a form of validation of the system. If enough people believe or pretend that their vote makes a difference, then the system is legit.

This is why communist countries had (and still have) close to 100% turnouts to cast a yes vote to the single candidate of the single party and this is why the communists were touting the voter turnout numbers to the whole world: the turnout was the proof that they are more legitimate than the liberal democracies with their abysmal numbers. But the numbers are not the problem, the expectations of the voters are. The problem is that an ever increasing number of people realize how pointless the whole process is, that their vote does not mean much and that even elected politicians are powerless against the entrenched power of the bureaucracy. An ever increasing number of people do not vote out of complacency. They just have no interest in politics. They have no meaningful information about politics, they have no idea what they would be voting for or against beyond the most banal political clichés they may pick up about each parties in the media. One could ask how would greater involvement of the ignorant and the indifferent result in better decisions? If anything, the number of the voters should be limited, not increased. In the early democracies such as Athens and Rome, only free citizens were allowed to vote. In the electoral systems of monarchies, voting rights were often restricted by various criteria. Maybe we could have better functioning democracies if we would restrict voting rights in some ways:

People who are completely dependent on the state have a strong interest to vote for those who promise them more of other people’s money. People on social assistance should not be allowed to vote.

People who work for the government have a strong interest in securing their own future by voting for candidates who promis to increase the size of the government. Civil servants and government contractors should not be allowed to vote.

People who work for any sort of government monopoly such as the health care industry, education and the government run parts of the energy sector have a vested interest in keeping their monopoly status. Nobody working in such industries should be allowed to vote.

People who are dependent on other kind of government benefits such as subsidized education, government guaranteed student loans or subsidized housing have a strong interest in maintaining those benefits. Nobody on a direct or indirect government benefit should be allowed to vote.

The members of the above groups share a fundamental conflict of interest. With their votes they can provide a measurable and personal financial benefit to themselves. The beneficiaries of the Robin Hood state are quite likely to vote for more ‘Robing of the Hood’ for their own benefit.

Democracies and politics in general is about finding ways to make collective decisions about our shared affairs. In the democracies of the developed world most of the decisions are about the redistribution of the collective wealth and income. Most developed countries have around 50% of their GDP spent by the government. It seems reasonable to suggest that only the providers of that income should have a say in how it is spent, not its beneficiaries. If you did not pay into the system, you should not have a say in how it is run. Voting should be a privilege, not an automatic right and definitely not an obligation.

Qualifying voters

If we can think about qualifying politicians, why not voters? Let’s suppose, that the voting process is just a tiny bit more complicated: before you can cast your vote, you have to fill out a questionnaire just to prove – let’s say – that you understand what exactly each party stands for. That you understand the issues. That you know the difference between debt and the deficit. That you understand enough English (or French) to understand what you are asked. Basic things. Just enough to ensure that you are an informed voter.

Direct democracy

How about a little Swiss style direct democracy? In the age of the internet, we could have quite a bit of it. We could easily create an on-line citizens’ panel of qualified voters to act as a shadow parliament. We definitely have the tools for it. We could have non-binding referendums on every single issue the parliament is voting on. We could have the budget voted on every single year on-line by all eligible voters. It would be interesting to see, for example, to what degree the votes of MPs would be in sync with the voters of their ridings. How much actual power we could give to such body could be open for discussion, but whatever the degree is, the very existence of such forum would be a serious boost to political participation and the feeling of engagement in our affairs. Direct democracy is possible and it does not have to be an all or nothing proposition.

Controlling the bureaucracy and the government

The greatest source of apathy about politics is the understanding that real power in politics is not in the hands of elected politicians but that of the unelected bureaucracy and the excessive spending of the government. What can we do about that? I think we could do plenty:

Balanced budget amendment

Two consecutive deficit budget should automatically trigger a general election or a binding referendum asking the electorate if one should be called.

Handicapping parties that overspend

An alternative to the above could be a system where if a governing party cannot produce a balanced budget, it should be handicapped in the following election.

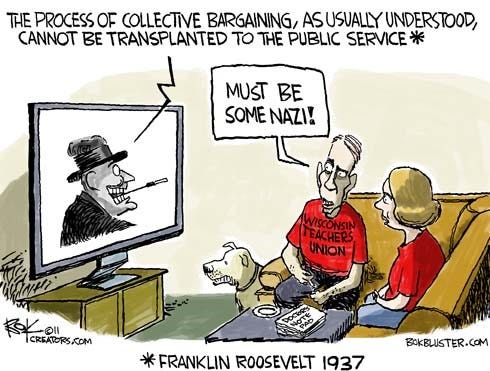

No public service union amendment

The existence of public service unions is a fundamental conflict of interest. Even the greatest champion of labor unions, Franklin D. Roosevelt was opposed to them saying that "All Government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service [ …….. ] It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management."

Absolute and complete budget transparency

In a Canadian context this would mean the elimination of the transfer payment system. “Transfer payments” is not a legitimate spending category but a cover up. Transfer payments should have a break-down with links to the budgets where they show up as revenue items.

Absolute and complete spending transparency

How the government spends our money should be accounted for to the last penny. The sunshine list is not enough. If you want to work for the government, you should have no right to privacy as far as your work is concerned. All of your benefits and every one of your actions and decisions should be open to scrutiny.

Handicapping politicians who voted for ill-conceived projects

The decisions of the parliamentarians should be made personal. Politicians should have responsibility for the things they voted on. Nobody, who voted for the long gun registry should be allowed to run for office again. Not for championing the idea, but for allowing the cost overruns. Politicians who voted for a project that has more than 100% cost overrun should be disqualified from running again.

Making contractors of government services responsible for project cost overruns

A similar policy should be made into law about private contractors. If a contractor cannot complete a project within reasonable time and cost overrun limits, it should not have the right to ever bid on a government project again.

Making bureaucrats personally responsible for their work

While the above two suggestions would go far in improving the working of governments, they are insignificant compared to the benefits of similar policies targeted toward government bureaucrats. If a government bureaucrat could lose his job for not meeting the measurable targets of the projects he is responsible for, we would have a lot less government waste. It is said that in politics failure is success as it opens the door for demanding more funding. All we need to do is to turn this around. Any sort of penalty system for waste would create immediate improvement in fiscal discipline. Public service should be what the name implies: SERVICE, not a guaranteed ticket to the gravy train.

Conclusion

The list above is a little raw and incomplete. I am sure you can give me enough new ideas to double it (which I invite you to do). I also realize how many of them are politically unviable. The point of the above ideas is to illustrate what the problems are, and how some of them could be ameliorated. The ideas above would do FAR MORE for a well-functioning democracy than any reform aimed at changing the way we are counting the largely irrelevant votes. Legitimizing the system further is not what will improve it. This isn't exactly a libertarian post. We should work on reducing the size and the impact of government, not to make proposals to make it work better. Still, it could be a legitimate libertarian strategy to champion policies that (like some of the above) would expose the problems of the de facto socialism we have to live with. The problem with socialism, as Margaret Thatcher pointed out, is that sooner or later you run out of other people’s money. The problem with representative democracies is that on the long run, they tend to move toward socialism. The only way to turn it around is to expose its problems and that should be a libertarian project. Because no one else will do it.

What we have to correct is not a deficit of democracy but the deficit of imagination addressing its problems.