As I was writing my last post, at some point I had to face a decision about its focus and direction.

The post was about the dangers of aiming for the middle with equity. Education is the best example of the point I was trying to make, but it was just that, an example. It left the question of what education could be, wide open. I cannot leave it that way.

However much it is needed, the world is not ripe yet for a true educational revolution.

The world, I’m afraid, is not even ready for an honest discussion about it, but a discussion we must have. Western social democracies have a few taboo subjects, education, health care and social security being the three most prominent. We can talk about them, but we cannot question the foundational idea, that they should be universal, uniform and government controlled.

We consider our ‘rights’ to these services the cornerstones of civilized existence. I can notice this most when I’m talking to people on the political left. They become very agitated when I start questioning the state’s role in any of them.

The first modern advocate of compulsory education was Martin Luther. His goal was to make sure that everybody could read the bible. The original intent, the very starting point was indoctrination. The goal is still that, the making of good citizens.

Government run social security and health-care was introduced by another German, Otto von Bismark.

If adaptation is a measure of success, then having these three (education, social security and healthcare) in full control of governments is probably the most successful idea in history.

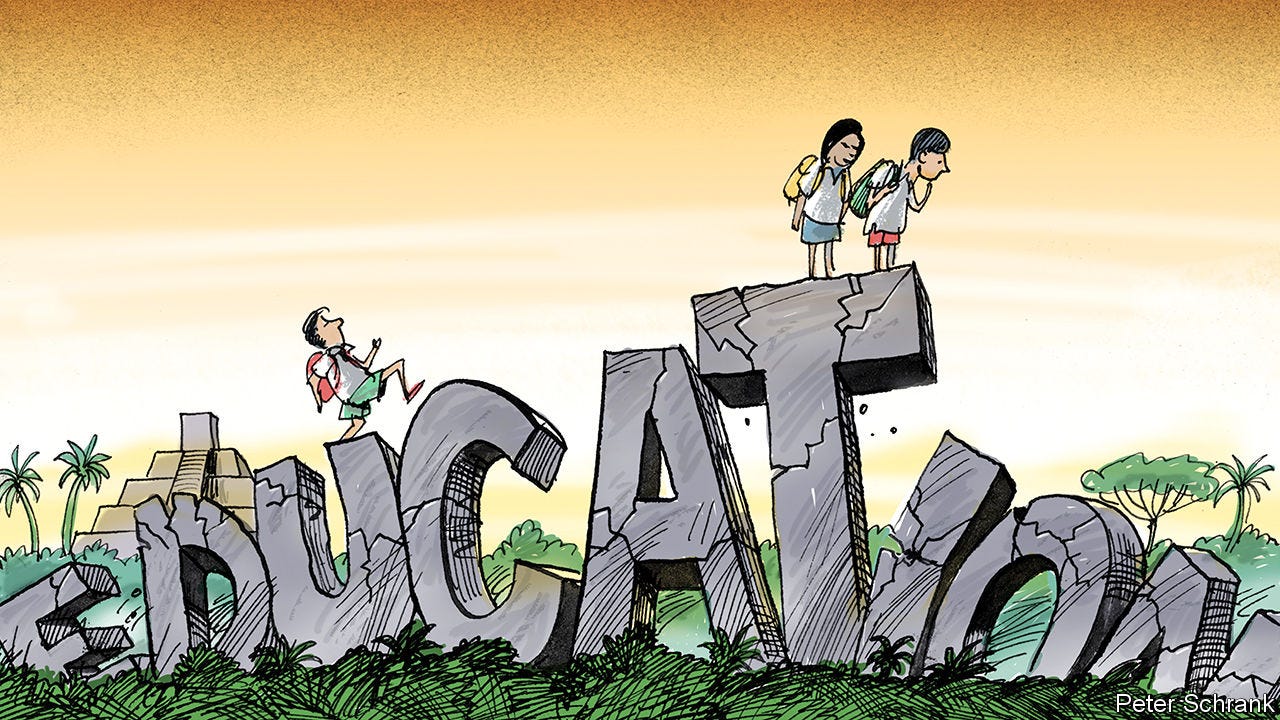

Yet, after a few centuries, they are crumbling everywhere. The social security Ponzi scheme is on the road to collapse; our health is getting worse, not better (at an ever-greater expense) and educational outcomes are not getting better either.

When talking about education, the fixing of the crumbling edifice should start with the lost questions of meaning:

What is education? Why do we need it? Why should it be controlled? Who should educate and how? What should be its subjects, methods, direction, focus and goal? Should it be measured, and if yes, why and by who?

Should we have national plans? Whether yes or no, why? Should that plan be uniform? Why?

Who should pay for it, why and how?

Luther wanted indoctrination.

The industrial revolution needed trainable workers with some basic knowledge.

The nation states needed a culturally coherent citizenry.

What do we need today, in the 21st century?

Who should be the ultimate beneficiary of education? The individual or the state/society?

The answers to these questions should imply directions. If the answer is both, then the question is: which should dominate? How can we apportion the balance between rights and responsibilities?

There could be hundreds of answers to these questions, but the only one that matters, is:

Why don’t we ask the questions? Why do we live with a monolithic system that was created to answer the needs of a different epoch?

The most important influence on my views was a speech delivered at Oxford University back in 1947 by Dorothy Sayers: “The Lost Tools of Learning” She was talking about medieval education:

“The syllabus was divided into two parts: the Trivium and Quadrivium. The second part—the Quadrivium—consisted of “subjects,” and need not for the moment concern us. The interesting thing for us is the composition of the Trivium, which preceded the Quadrivium and was the preliminary discipline for it. It consisted of three parts: Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric, in that order. Now the first thing we notice is that two at any rate of these “subjects” are not what we should call “subjects” at all: they are only methods of dealing with subjects.” (emphasis mine)

She offers many excellent examples, and finishes her speech with this:

“The combined folly of a civilization that has forgotten its own roots is forcing them to shore up the tottering weight of an educational structure that is built upon sand. They are doing for their pupils the work which the pupils themselves ought to do. For the sole true end of education is simply this: to teach men how to learn for themselves; and whatever instruction fails to do this is effort spent in vain.”

What would I like to see? Teaching kids how to learn. How to ask questions and how to find answers. Not what to think, but how to think. Nurturing curiosity and creativity. Exposing them to ideas by connecting them to examples in the real world. Teaching them concepts, not just facts.

Teaching them how to compete and cooperate.

But all of these are just feelgood clichés. Trivialized ideals. They are not actual curricula. As Sayers points out:

“Subjects” of some kind there must be, of course. One cannot learn the use of a tool by merely waving it in the air; neither can one learn the theory of grammar without learning an actual language, or learn to argue and orate without speaking about something in particular.

In the world we are living in, everybody is susceptible to reigning paradigms and intellectual trends. Including our teachers.

On the top of that, there is a system of competing interests.

Education is captured by those interests. What makes that capture possible, is political control over the system. The only way to reform education is by removing politics from it entirely.

I made the points in my last post, that K12 should be paid for by an unconditional voucher system based on the cost/student of the public education system. With the removal of the government shackles, I would expect a great variety of methods in teaching the lower grades (1-8), and a great variety of subjects in grades 9-12.

What those subjects could be?

Let me start with what it shouldn’t be:

I know a recently retired high school English literature teacher who went to a bookstore in August every year, picked up a recently published book that struck his fancy and made it to the subject of his first semester. He didn’t even try to find the most critically acclaimed, or commercially successful. I was shocked and horrified when he told me. No history of literature, no books that withstood the test of time.

Just the latest whatever. That is not education. It could hardly pass for baby-sitting with story time.

Literature should be thought as literary history.

Same for music and the fine arts

History should be taught as civilizational evolution, not as an unending list of names and dates of events.

Science should be taught as the history of scientific paradigm shifts.

Basic statistic and data analysis

Basic concepts of economics, finance and accounting.

Basic concepts of philosophy and religions

Logic, reasoning and its fallacies

Ethics and human psychology

There should be courses about agriculture, farming and ecology.

About health and human biology, nutrition, etc.

About natural resources, their extraction, geography and importance.

About geopolitics

About basic concepts of engineering

About military history and its evolution

About the evolution of political systems, their pros and cons.

Like everything else on Substack, this is a reader supported publication.

You can help it by following or subscribing.

You can engage with it by clicking on like and/or commenting.

A ‘like’ costs nothing and is worth a lot.

You can help this Stack grow by sharing, recommending, quoting or referencing it.

You can support it by pledging your financial support.

Any and all of it will be much appreciated.

Even I could draw up a curriculum for any of them. The common element is the focus on concepts. High school education should be about the understanding of the world we are living in. The details should be just illustrations of the concepts.

The list above is not complete, and clearly, they cannot all be thought in one school. We could have high schools focusing on the arts (as we already do), on athletics and languages or any subset of the list above.

K12 schools will have to compete on how and what they are teaching, on how successful they are in engaging the children and gain the trust and satisfaction of the parents. Schools could exist divided over gender and ethnic lines.

Higher education should be paid for with scholarships and Grants. Overall support may come from private donations and endowments, never from governments.

I could even support a system where government scholarships would pay for full tuition of the top performing 5%, and maybe half for the next 5%. These numbers are just examples, but I am sure you get the idea that you either have to pay, or be the best.

Grants, scholarships and private loans are available already, they can easily replace overall public funding. Useless courses in the humanities would disappear in no time if they had to rely on parents paying for them.

I could go on dreaming about the possible roles of educational technologies such as AI assisted and online courses; standardized, national online testing and so on, but the important point is this:

Real change cannot take place in a sclerotic, bureaucratic, top-down system.

It has to be decentralized, control – and it must be emphasized: full financial control - over it must be given back to individuals.

Individual students (their parents) and individual schools.

How to achieve that is the only question that is worth talking about.

With a voucher system the camel nose of the state is already well under the tent.

I agree with pretty much everything you said, apart from your characterisation if Luther, but fear that unless we let go of the idea that it is somehow the responsibility of society to educate children, which is what a voucher implies, we will not get the results you and I are aiming for.

Some good news:

https://fee.org/articles/4-reasons-why-todays-new-private-schools-are-different/