What prisons should be about

I spent 3 months and 20 days in police custody and jail, 5 months and 10 days in a real prison. The ‘big-timers’ said I only went in to look around. They were right. I am not a criminologist, I only glimpsed into the system, but seen enough to have clear ideas about it.

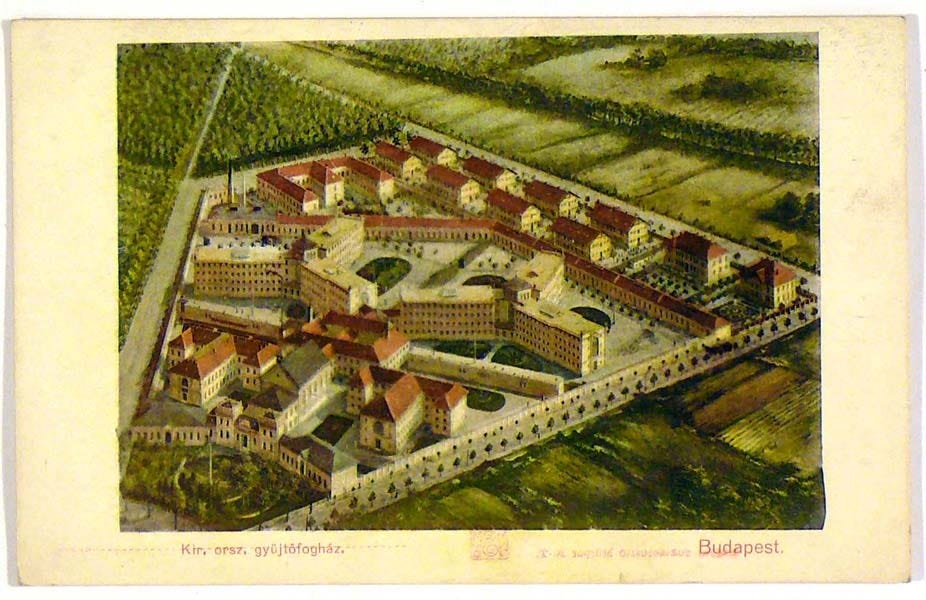

The jailhouse

Once our investigations were completed, we were sent to the courthouse jail. Later, in the prison itself, we were separated from the ‘common’ criminals, but the court jail could not afford such luxury and we were mixed in with everybody awaiting trial. The distinction between political and ‘common’ criminals was an important part of the system. Political prisoners were kept apart from the rest to protect the later from being infected by subversive ideas. In the police lock-up and the court jail I got acquainted with a fascinating variety of criminals, getting some insight into their attitudes and motivations. The most memorable encounter I had was with a young gang member. Around the time we were in, an investigation of a youth gang was just wrapping up. They were in for a series of typical youth gang crimes: break-ins, robberies, assaults and rapes. I spent a few weeks with two members of the gang on separate occasions. I recognized one of them later in a movie made in 1993 – Menace II Society – in the character of O-dog, played by Larenz Tate. Now that I think about it, his friend in the movie played by Tyrin Turner could have easily been my other cellmate from the same gang. (Save the skin colour, of course) The first was lively, friendly, and personable but without any morals, any conscience, any guilt for anything he did. No loyalty either. He was singing like a canary on his fellows, he was to be the star witness of the case. Why? Because the cops promised him to be nice to him if he did. How did we know? He told us. I cannot remember how the subject came up in the conversation, but at some point he said: “It’s too bad that we cannot get guns around here. If I had a machine gun, I would get on a street car, shoot everybody and take their valets and purses” This was his fantasy. His dream, thwarted only by the lack of machine gun availability. The frightening part of that moment was that I believed him. I still do. He was serious and believable. I could perfectly imagine him to kill someone for the change in his pocket if he could just get away with it. I recommend the movie highly; I have not seen a better representation of the world of crime, one that comes closer to my personal experiences.

Lesson #1

You CANNOT reform, rehabilitate or correct the behaviour of a sociopath. THERE ARE people in this world, who are incorrigible. THERE ARE people who feel no empathy, no remorse, no regret over the harm they cause to others. The only thing that works with people like this is credible deterrence and iron-fisted, merciless retribution.

I have met several other interesting criminals from the mugger and the rapist, the embezzler and the gypsy knife fighter to the professional bank burglar (who was taken away several times during our time together to create educational videos for police training) but their stories would not add to the points I am trying to make. Once our sentences became final we had to start our sentence in a real jail.

The prison conditions

Hungary at the time had four degree of severity in the system (fogház – börtön – szigorított börtön – fegyház) the last one roughly translating to a maximum security prison. All political prisoners were kept in maximum security prisons. The designation didn’t have much to do with security, the differences were in the level of privileges that prisoners were allowed to have:

Visit Parcel (3kg) Letter Commissary

Fogház (jail L1) 1 / month 6 / year 2 / month Ft 200 /month

Börtön (jail L2) 1 / 2 months 4 / year 1 / month Ft 150 /month

Szigorított börtön 1/ 3 months 2 / year 1 / 3 months Ft 120 /month

(Prison)

Fegyház 2 per year 1 per year 2 per year Ft 100 /month

(Max. sec. Prison)

100 Forint at the time bought me 20 packs of the cheapest cigarettes or 1kg of smoked sausage. Cigarettes were the black-market currency. The basic rules were pretty much the same as they are in American or Canadian jails with some exceptions. These exceptions regulated access to information. The most severely punished infraction was contact with the outside world. Finding a newspaper, an amateur radio on your person or in your cell meant 20 days solitary and the likely loss of your parole. Still, there was a lively black market for ingenious tiny radios – starting price: 20 packs of cigarettes. I will not comment on the irony of the yearning for government controlled communist radio broadcasts. It was more than what we had inside. Twice a week we had the prison radio news and once a week we got the ‘kübli zeitung’ or ‘Loo Courier’ with all the news our jailers saw fit to share with us. We saw a movie every 3 months. I was in long enough for only one twenty minutes visit from my mother. Letters were pointless. 28 lines, anything beyond that was blacked out with a marker. Any content that was forbidden was also blacked out. I could only correspond with one designated person who had to be a relative. The only acceptable content was personal: “I am fine, how are you, how is uncle Joe and how was cousin Susan’s wedding.” Minor infraction (talking back to a guard or disruptive behaviour) was punished by withdrawal of benefits such as letter and visit privileges while more serious ones such as fighting or possession of anything forbidden was punished more severely, typically by solitary confinement. The only thing worse than solitary was the dark room, where you were locked up in total darkness, the only indication of time being the meal you got and the cot getting lowered. During the day it was attached to the wall as it was not allowed to sit down, not even on the floor. If the guard caught you sitting, they poured water onto the concrete pen that was the floor of the cell. The deterrence effect of these punishments went a little beyond the unpleasantness of the experience itself. I knew, that if I get punished for anything, I can also kiss goodbye to my parole. I met only a few people who went in with the defiant attitude saying that they will not compromise to get a favour from the enemy. We had to work. The prison deducted the cost of our keeping from what we earned. The work was hard, but not oppressing. It kept us busy, very few people stayed away from it voluntarily.

The guards

I never had a conflict with the guards. Quite a few of them were Greek communists who came to Hungary to escape persecution at home. They took the job for the promise of citizenship. They had lots of power, but I did not see them abusing it nor did I hear of abuse from others. They did not have to be abusive personally, the system was abusive enough.

The people

I was surrounded by political prisoners. Spies, priests, rebells. On the other hand, you have to keep in mind, that it did not take much to become part of that elite club. Just think of my case. What I was in for. I was working with an 18 year old guy who got three years for writing a letter to radio free Europe offering his services (whatever that meant). He was 17 when he did it, he was tried as an adult. There were two gypsies, who broke into the village grocery store, got drunk and fell asleep. That would not be political yet, but while drunk, they took Lenin’s picture off the wall and shat on it. That got them a few years as political prisoners. There were some bad guys there as well, one of them being a cell-mate of mine for four months. He was an internment camp capo during the war, doing anything he was asked to do. He escaped detection after the war, turned coat and became the bloodiest communist. At some point he must have rubbed someone who knew about his past the wrong way, he was renounced and tried for his war-crimes, ended up with a 13 year sentence, no parole. He was fifty something at the time and into the eight year of his sentence when I shared a cell with him. He was still a bloody communist. He did anything he could to serve his new masters. Not to gain favours, but from his genuine desire to serve whoever the master with power happened to be. He took his punishment in stride, trying to prove himself to his new masters, licking their boots even more ferociously. No punishment would have worked on this guy with unquestioning servitude to anyone with power. He had no conviction, no personality, no opinion on his own. The ultimate henchman. He was the most disgusting snitch costing the parole to many, including one of my case-mates. Some fifteen years later I realized that I was also to blame; the snitch overheard and reported on a discussion I had about said case-mate with my other cell-mate I had absolute trust in. I was not careful enough.

Lesson # 2

Irredeemable scum comes in many forms, shapes and sizes. There is no way to rehabilitate someone with this attitude, someone who would do anything for any master.

I met some wonderful people as well, the soldier who got eight years for trying to sabotage the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the working class hero who got 10 years for trying to get ready for another 1956 style revolution. They did not want to start one, just wanted to get ready to support a democratic change with guns if needed.

The main lesson

I found nothing wrong with communist Hungarian jails. They were pretty much what jails are supposed to be about. Punishment and deterrence. What was wrong was the law that put me there and the corrupt justice system that facilitated the process. It matters far less what jails are like than it does what kind of people you put into them. Most of the people I met shouldn’t have been there. For those who should, the conditions were appropriate.

Good laws are the most crucial part of a just system.

Predictable and consistent application of those laws comes second.

Jails are only tertiary in importance but even if we have the right people there for the right reasons, we need to know what to do with them. We need well defined , proven principles. I do not think that we (meaning western democracies) are doing a very good job.

Deterrence and punishment vs prevention and rehabilitation

The foundation of the prevailing philosophy of the criminal justice system is the idea that since we are not entirely responsible for our conditions, we cannot be entirely responsible for our actions that were influenced by those conditions either. That instead of holding the criminal responsible for his decisions, we should change the conditions that influenced the decision. That instead of punishment, we should treat them as victims of their circumstances, their background, their mental or social conditions. That rehabilitation means exactly that, the healing of a sick person, the healing of the conditions that created him. Correctional services are developing into a branch of social services giving employment to an ever widening group of professionals eager to get on the government payroll with the next great idea to ‘heal.’ We are also still enamoured by the progressive idea that human nature can be changed and since such thing is possible, we should never give up trying to do it. I consider this prevailing attitude toward criminals inhuman and demeaning. By absolving them from responsibility for their actions to any degree means that we are considering them sub-human to that degree. Being human means to take responsibility for who you are and what you do, regardless of what led you to the place and point in time when you have to take responsibility for your actions. I do not believe in prevention and rehabilitation because I don’t think that either is possible. There is no evidence to show that it is. I challenge anybody to prove otherwise. I also respect criminals and believe that like any other human they are not just mindless products of their circumstances. That they know right from wrong and that being fully human means that they have to be responsible for their actions.

The failure to deter

Shortly after I arrived to Paris in 1979, I read an article of Alain Peyrefitte then Minister of justice of France talking about the effectiveness of a criminal justice system. He pointed out how the deterrence value of criminal law is jeopardized by an unpredictable process. He talked about the criminal calculus, about all the points that could possibly improve the chances of the criminal, about all the things they take into consideration before committing a crime.

A criminal never starts with the assumption that he will be caught.

Once he is, there is a chance that something will be screwed up with the process in his favour.

There is a chance that not all evidence will be found.

There is a chance that get a good lawyer can get him off, or plea-bargain the punishment down to nothing.

Even if he gets convicted, the judge is allowed serious latitude in the sentencing

Once sentenced, the parole system will put another layer of variation into expected seriousness of the penalty.

Then with all that they end up in a system that is not all that bad. The food is good, the health care is excellent, entertainment is great, they can spend time with their buddies. Get married and have kids, get a university degree or two. Get an education on becoming a more successful criminal next time around.

Even if the chances are 50-50 for each of the above, the end result is not that frightening. The Peyrefitte argument made perfect sense to me. From the first impressions I got from the western penal systems I realized that they are not designed to deter. In order to do that, there should be a lot more direct connection between the crime and the punishment. A far greater certitude from the second step on from the above list. An acquaintance of mine who is supplementing his welfare with shoplifting ever since I know him spent one night in jail after his seventh conviction. Why would he stop?

Understanding punishment

I clearly do not subscribe to the rehabilitation philosophy of penal systems. It would be a good question why – because of my personal experience described above or because what I think of free will and personal responsibility as a libertarian? I don’t think even I can answer that. What I can tell you, is what I felt to be the punishment: I suffered the most from having no access to music. I would have suffered probably even more if I did not have the chance to read – which luckily was not the case. Lack of news, lack of communication with the outside was hard on me. Lack of communication in the inside would have been harder. Sometimes the food was bad, but in the end I gained weight in 5 months I hope you can see the trend. We are social animals. Taking the possibility of social interaction away from us is the hardest punishment. In today’s super-connected world I imagine it would be even harder. It is not torture, it is not cruel, so why don’t we use it? The only answer I can imagine is because we do not want to punish. We want to ‘heal’, ‘correct’ and ‘rehabilitate.’ Like with many other aspects of our society we are trying to fix inequality with redistribution. Am I alone to think that morality redistribution will not work either? That being institutionally ‘good’ to criminals will not make them better people? In the end, the prison sentence worked on me. It did what a jail is supposed to do. Made me not to repeat what got me there in the first place. It thought me to be more careful, to avoid any conflict with the authorities, not to be cocky, to be more analytical and more critical of the system without any open opposition. It was the first step on my road out of the country. It thought me that communism was not the place for me. The criminal justice system is a service to society. Its function is to remove the harm and to prevent the hurt. For most people looking in from the outside, prison conditions look more like a reward than a punishment. We maintain a system that does not deter, that does not punish, all it does is the temporary removal of the harmful elements – and it does not even do a good job with that. I think it is time to stop this failing experiment; it is time to change direction, it is time to turn back to an approach where the state punishes, civil society rehabilitates but in the end leaves it to the individual to change and redeem himself. I will leave you with this much, but I will return to the subject trying to put into form what I would consider to be an equitable and effective criminal justice and penal system.